In October of 1921, a little-known forester and regional planner from Connecticut put forth a revolutionary idea.

“What is suggested is a ‘long trail’ over the full length of the Appalachian skyline,” Benton MacKaye wrote in an article published in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects.

Before proposing his bold blueprints for the nation’s first end-to-end Appalachian footpath, MacKaye had encountered what many would call a rough patch in his life.

“What is suggested is a long trail over the full length of the Appalachian skyline.” —Benton Mackaye, 1921

Myron Avery (right) discusses a trail marker (Courtesy of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy)

“To say that MacKaye’s life at this point was not going well would be to engage in careless understatement,” wrote Bill Bryson in A Walk in the Woods, his New York Times bestselling novel about his own experiences along the Appalachian Trail (recently adapted to screen by Robert Redford). “In the previous decade he had been let go from jobs at Harvard and the National Forest Service, and eventually, for want of a better place to stick him, given a desk at the U.S. Labor Department with the vague assignment to come up with ideas to improve efficiency and morale. There he dutifully produced ambitious, unworkable proposals that were read with amused tolerance and promptly binned.

In April 1921, his wife, a well-known pacifist and suffragette named Jessie Hardy Stubbs, flung herself off a bridge in over the East River in New york and drowned.”

It was in the midst of failure and despair that MacKaye revealed his notion for an uninterrupted footpath stretching from north Georgia to Maine to a friend named Charles Harris Whitaker, who also happened to be the editor of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects.

The Appalachian Trail of today stretches some 2,189 contiguous miles from the forested summit of Georgia’s Springer Mountain to the knife-edge peak of Katahdin in Maine, but MacKaye’s initial vision laid out a different path.

He thought the trail should begin on New Hampshire’s Mount Washington, the highest point in the northern Appalachians, and culminate atop North Carolina’s Mount Mitchell, the highest point east of the Mississippi River.

He envisioned an uninterrupted footpath along the spine of the Appalachian Mountains with intermittent shelters along the way, much like the A.T. that exist today, but his broader goal for the trail was different from what it would eventually become. “Community groups,” he said, would be sure to “grow naturally out of the shelter camps. Each would consist of a little community on or near the trail where people could live in private domiciles.”

AVERY’S LEGACY

If it was Benton MacKaye’s foresight that brought the possibility of an Appalachian Trail into the forefront of the American consciousness, it was the logistical prowess of a maritime lawyer and Washington D.C. native named Myron Avery that brought it to life.

“MacKaye was a vision guy,” said Appalachian Trail Conservancy C.E.O. Ron Tipton. “The trail would have been impossible without his foresight, but Myron Avery became totally obsessed with it and saw the whole thing through until its completion.”

An avid hiker himself, Avery took over essential tasks like mapping trail routes and organizing the volunteer support needed to carve a path through some 2,000 miles of rugged, undeveloped wild lands.

But he brought a hard-nosed approach to the task of making the Appalachian Trail a reality.

A.T. scouts in snowshoes stand on a snowy overlook near the Smokies (Courtesy of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy)

Bill Bryson describes Avery as a doer, unafraid of upsetting or offending the people between him and his goal. According to Bryson, Avery forged two paths between Georgia and Maine. “One was of hurt feelings and bruised egos,” he said. “The other was the A.T.”

“Initially, MacKaye and Avery were allies,” says Ron Tipton of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. “The falling out came when the federal government began forming Shenandoah National Park and constructing Skyline Drive.”

MacKaye opposed the now famous scenic byway because it interrupted the path he hoped the Appalachian Trail would follow through Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. He also thought it would compromise the natural integrity of the land.

Early hiker with walking stick leans on a white-blazed tree along the trail (Courtesy of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy)

But Avery took a more practical approach to the government’s construction of Skyline Drive. He decided to work with the feds and reroute the trail, accommodating their new road.

It was at this point that MacKaye quietly faded from the scene, and by the time it was completed in 1937, the two fathers of the Appalachian Trail were no longer on speaking terms.

Avery’s vision for what the Appalachian Trail would eventually become was more in line with the world famous foot path that exists today.

He believed the A.T. would revolve around hiking and that it would be sustained by hike-centric groups like the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.

MacKaye’s vision of self-sustaining mountain top ‘community camps’ where nerve-shattered urbanites could seek a healing wilderness respite never actually materialized, but the regional ribbon he hoped would hold it all together endured as one of the world’s most iconic symbols of adventure and perseverance.

Myron Avery (center) at Katahdin circa 1933 (Courtesy of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy)

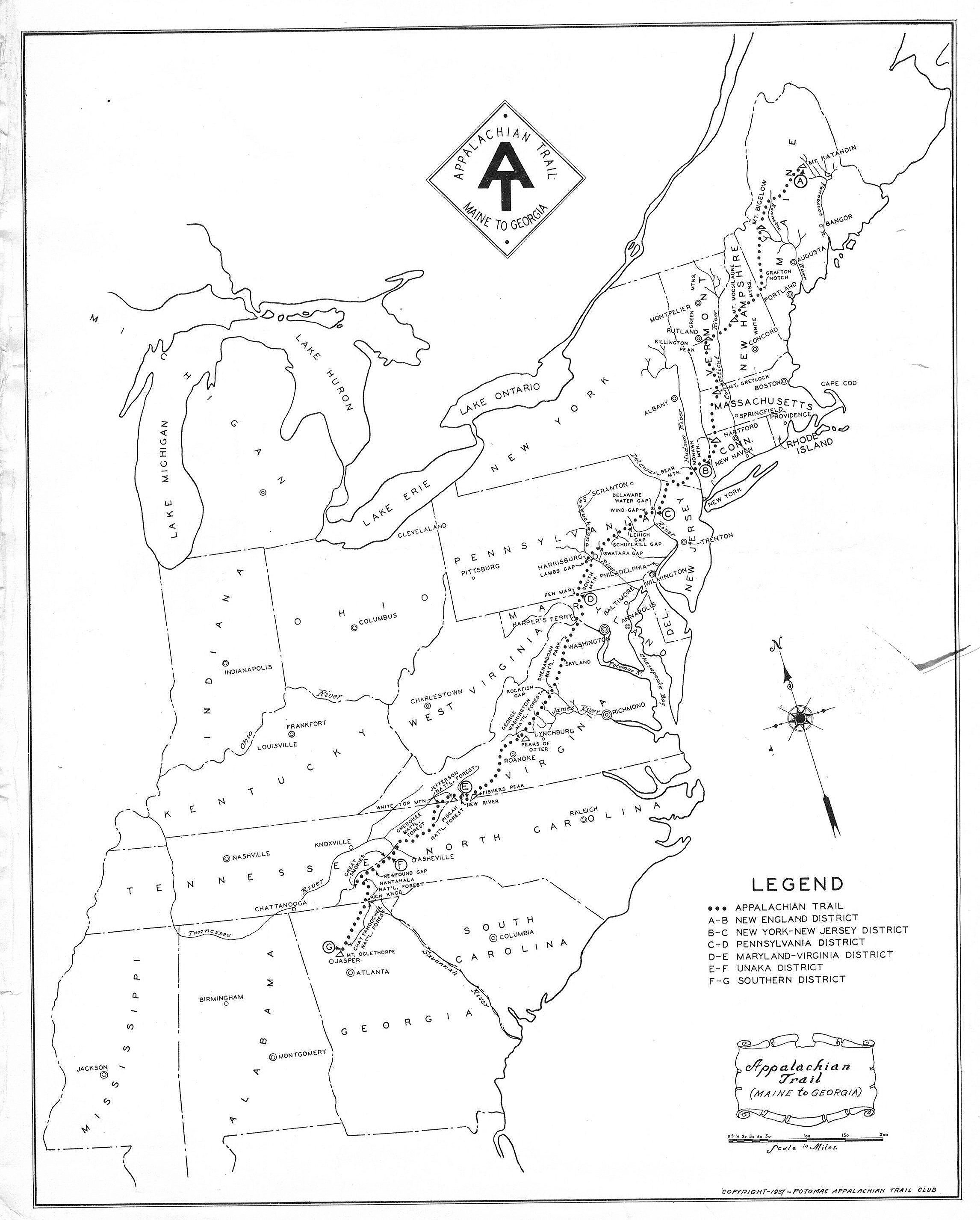

Map of the original Trail as proposed in 1937 (Courtesy of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy)